Terms and Conditions

1. Introduction

2. Intellectual Property Rights

3. Restrictions

- publishing any course material in any media;

- selling, sub-licensing and/or otherwise commercializing any course material;

- publicly performing and/or showing any course material;

- using the online classroom in any way that is, or may be, damaging to the online classroom;

- using the online classroom in any way that impacts user access to the online classroom;

- using the classroom and courseware contrary to applicable laws and regulations, or in a way that causes, or may cause, harm to the school, or to any person or business entity;

- engaging in any data mining, data harvesting, data extracting or any other similar activity in relation to the online classroom, or while using this Website;

- using the online classroom to engage in any advertising or marketing;

Certain areas of this Website are restricted from access by you and Insurance License Online, LLC may further restrict access by you to any areas of this Website, at any time, in its sole and absolute discretion. Any user ID and password you may have for this Website are confidential and you must maintain confidentiality of such information.

4. Your Content

5. No Warranties

6. Limitation of Liability

7. Indemnification

8. Severability

9. Variation of Terms

10. Assignment

11. Entire Agreement

12. Governing Law & Jurisdiction

13. Refund Policy

Quick Links

-

Home

-

About Us

-

How it Works

-

Licensing Information

-

Contact us

-

Continuing Ed (CE)

Our Courses

-

Property & Casualty

-

Customer Representative

-

Certified Adjuster

-

Life, Annuity & Health

Get in Touch

Follow Us

Copyright © 2025 Insurance License Online | All Rights Reserved.

What would you say is the cornerstone of professionalism in the insurance industry?

ETHICS

Claims Adjusters are required to complete how many hours of continuing education every two years?

24 HOURS

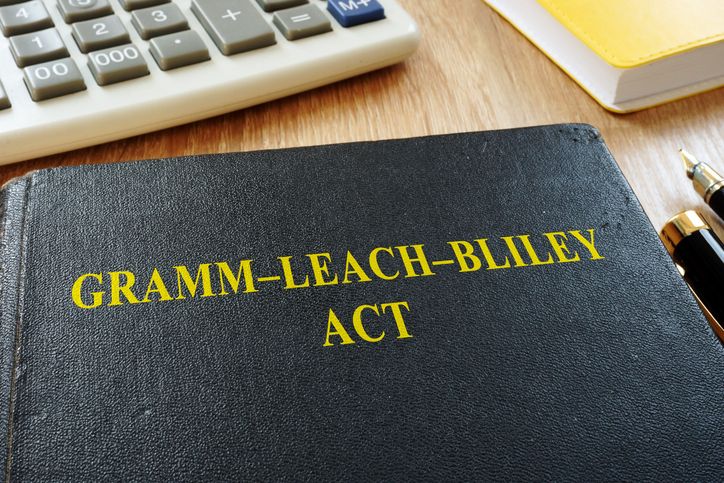

The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act requires you and your company to ensure the confidentiality of your customers' personally identifiable information and financial information. What was this referred to in this course?

PROTECTING CLIENT DATA

Sunshine Insurance Company’s Security Program

Notification of Privacy Practices: When you become a client of Sunshine Insurance, you will receive a comprehensive privacy notice. This document details the types of personal information we collect, how we use it, and with whom it may be shared. It also outlines your rights, including the option to opt-out of certain information-sharing practices.

Protecting Your Information: We employ robust physical, electronic, and procedural measures to secure your personal information. This includes secure servers, encrypted communications, and controlled access to client records. Our staff undergoes regular training to stay informed about their responsibilities under the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) and to handle your information with the utmost care.

Information Sharing Policies: Sunshine Insurance does not share your personal information with non-affiliated third parties for marketing purposes without your explicit consent. We carefully vet and monitor any third-party service providers who may have access to your information, ensuring they comply with GLBA regulations.

Handling Inquiries and Complaints: Our dedicated team is available to address any questions or concerns you may have about our privacy practices. We are committed to compliance with GLBA and will promptly address any issues related to the handling of your personal information.

Annual Privacy Policy Review: Sunshine Insurance conducts an annual review of our privacy policies and practices to ensure ongoing compliance with GLBA. We update our privacy notices to reflect any changes in how we collect, use, or share your information.

Commitment to Privacy and Compliance: At Sunshine Insurance, our adherence to GLBA standards underscores our commitment to protecting your privacy and maintaining legal compliance. This dedication not only builds trust with our clients but also ensures that we maintain a high level of professionalism. You can feel confident that your sensitive information is secure, and our company is shielded from the legal and reputational risks associated with data breaches or non-compliance.

Internet Security Checklist for an Insurance Company

Secure Network Infrastructure

- Ensure the company’s network is protected with firewalls.

- Regularly update and patch routers and switches against vulnerabilities.

- Install and maintain updated antivirus and anti-malware software on all devices.

- Conduct regular scans for threats and address any detections immediately.

- Encrypt sensitive data both in transit (e.g., emails, online transactions) and at rest.

- Utilize secure protocols such as HTTPS for web-based transactions and communications.

- Implement strong, unique passwords for all systems and accounts.

- Require periodic password changes and use multi-factor authentication where possible.

- Keep all software, including operating systems and applications, up to date with the latest security patches.

- Conduct regular training sessions for employees on cybersecurity best practices.

- Keep staff informed about the latest phishing scams and social engineering tactics.

- Use email filtering tools to block spam and phishing emails.

- Train employees to recognize and report suspicious emails.

- Limit access to sensitive data based on employee role and necessity.

- Use access controls and auditing to track who accesses what data and when.

Regular Backups

- Regularly back up critical data and store backups in a secure, offsite location.

- Test backup restoration processes periodically.

Incident Response Plan

- Develop and maintain an incident response plan for potential cybersecurity events.

- Conduct regular drills to ensure preparedness.

- Use web filters to prevent access to malicious websites.

- Keep browsers updated to the latest version.

This checklist should be reviewed and updated regularly to adapt to new cybersecurity threats and technologies.

Farrell v. Grand Canyon Fasteners

After the accident, Emily experienced both tangible and intangible losses. She suffered a broken leg and severe back pain, leading to emotional distress and mental anguish. Emily filed a claim for her medical expenses for her treatment and rehabilitation. She also filed a claim for her physical pain and suffering, and the mental trauma caused by the accident.

General damages were awarded to Emily for the intangible losses she suffered, which are not directly quantifiable but significantly impacted her life.

- Pain and Suffering: For the chronic back pain and discomfort she endured post-accident.

- Mental Anguish: For the emotional distress, anxiety, and depression resulting from her injuries and the trauma of the accident.

- Permanent Injury: Emily’s back injury led to a permanent limitation in mobility.

- Loss of Reputation: As a graphic designer, her inability to work for an extended period affected her professional reputation.

Emily also received special damages for tangible and calculable losses directly resulting from the accident.

- Medical Bills: All her medical expenses, including surgery and physiotherapy costs.

- Lost Wages: Compensation for the time she was unable to work due to her injuries.

- Repair Invoices: Costs for repairing her damaged vehicle.

The court also awarded punitive damages against the trucking company. This was due to the company’s hiring practice of not pulling motor vehicle reports before hiring drivers; the court felt their conduct “demonstrated a gross disregard for public safety”. The punitive damages were intended to punish the trucking company and serve as a deterrent to prevent such negligence in the future.

Emily’s case illustrates the different types of damages that can be awarded in liability claims. Each type of damage played a crucial role in ensuring that Emily received fair compensation for the varied impacts of the accident on her life.

The Case of the Coffee Shop Slip and Fall

As Jane walked in, she slipped and fell due to the wet floor, suffering a severe wrist fracture. This injury not only caused her physical pain but also hindered her ability to work on her writing projects, leading to a loss of income.

Is Bean Delights legally responsible for Jane’s injury?

- Duty of Care: “Bean Delights” had a duty to ensure the safety of its customers.

- Breach of Duty: The coffee shop breached this duty by not taking appropriate measures (like placing caution signs or mats) to prevent accidents due to the wet floor.

- Cause of Injury: Jane’s fall and subsequent injury were directly caused by the coffee shop’s negligence.

Legal Relief for Jane

- Medical Expenses: Jane can seek compensation for her medical treatment.

- Lost Income: Compensation for the income lost due to her inability to work.

- Pain and Suffering: Jane can also claim damages for the physical pain and mental distress caused by the injury.

In this scenario, “Bean Delights” is the tortfeasor as their omission (failure to address the wet floor hazard) led to Jane’s injury.

Jane decided to take legal action against “Bean Delights.” The court found the coffee shop negligent and liable for Jane’s injuries. “Bean Delights” was ordered to compensate Jane for her medical expenses, lost income, and pain and suffering, illustrating how tort law provides a remedy for those harmed due to others’ negligent acts or omissions.

This example of Jane’s accident in the coffee shop demonstrates the concept of a tort through negligence by omission. The coffee shop’s failure to take preventive measures constituted a breach of their duty of care, leading to Jane’s injury and subsequent legal claim for compensation. This scenario is a classic real-life illustration of how tort law operates, holding parties responsible for their wrongful acts or omissions that cause harm to others.

McDonald’s Coffee Case

Stella Liebeck was a 79-year-old woman from Albuquerque, New Mexico. She became widely known as the plaintiff in this lawsuit against McDonald’s. In February 1992, Liebeck purchased a cup of coffee from a McDonald’s drive-thru. While seated in the passenger seat of her grandson’s parked car, she attempted to remove the lid from the cup to add cream and sugar. In doing so, the coffee spilled onto her lap, causing severe burns. The coffee was served at a temperature (around 180-190 degrees Fahrenheit) that could cause third-degree burns in a matter of seconds.

Liebeck suffered third-degree burns on her thighs, buttocks, and groin area. She was hospitalized for eight days, undergoing skin grafting and other treatments. The recovery was long and painful, involving two years of medical treatment.

Initially, Liebeck sought to settle her claim with McDonald’s for $20,000 to cover her medical expenses and lost income. McDonald’s offered only $800, leading Liebeck to file a lawsuit. Her suit claimed that McDonald’s coffee was “defectively manufactured” by being too hot and more likely to cause severe injury than coffee served at any other establishment.

During the trial, it was revealed that McDonald’s had received numerous reports of similar incidents but had not changed its coffee temperature policy. The jury found that McDonald’s was 80% responsible for the incident and Liebeck 20% responsible.

The jury awarded Liebeck $200,000 in compensatory damages (reduced to $160,000 due to her 20% fault) and $2.7 million in punitive damages, the latter of which was equivalent to about two days of McDonald’s coffee sales. The judge later reduced the punitive damages to $480,000, leading to a total award of $640,000. However, the final settlement amount was less, as Liebeck and McDonald’s later settled out of court for an undisclosed amount (believed to be less than $600,000).

The case is often misunderstood and misrepresented in popular culture and media. It became a focal point in debates on tort reform and litigation in the United States, with many people viewing it as an example of frivolous litigation due to the nature of the accident and the seemingly large initial punitive damages award. However, legal scholars and others familiar with the details of the case often point out that it highlighted significant safety concerns and corporate responsibility issues, especially regarding the serving temperature of McDonald’s coffee and the severity of Liebeck’s injuries.

The Case of “Am I Too Late?”

Living in Florida, Jane was under the state’s legal framework, where the statute of limitations for filing a negligence claim is two years. This law mandates that any legal action related to personal injury due to negligence must be initiated within this two-year window from the date of the incident.

Upon filing her lawsuit, Jane encountered a significant legal barrier. Since she initiated her claim after two and a half years, she had exceeded the two-year statute of limitations set by Florida law for negligence claims. The law sets a strict deadline for filing lawsuits. In Jane’s case, the deadline was two years from the incident.

Because Jane filed her lawsuit after the prescribed two-year period, her case was legally barred. The court would likely dismiss her lawsuit on the grounds that the statute of limitations had expired, regardless of the merits of her claim.

Jane’s situation clearly demonstrates the critical importance of statutes of limitations in legal proceedings. Despite the validity of her claim against “Bean Delights,” her delay in filing the lawsuit resulted in a lost opportunity for legal recourse. This example underscores the necessity for potential plaintiffs to act promptly and be aware of the legal time limits within which they must assert their rights. Missing these crucial deadlines can lead to the forfeiture of the right to seek justice and compensation for injuries and losses incurred.

How Endorsements are Used

- Adding Coverage – “the insured adds towing and labor to her auto policy”

- Modifying Coverage to Conform – “Florida Property policies statutorily add Catastrophic Ground Collapse coverage”

- Changing Coverage – “the insured buys a car and adds the new vehicle to her policy”

Certificates of Insurance

If an insured has a policy bound and a Binder is given to the insured to evidence the new coverage this Binder acts as the insured’s “Proof of Insurance” until the actual policy is sent to the insured. Binders normally have terms of 30 or 45 days; in those instances, NO written notice of the termination of the Binder will be required to be provided to the insured. However, in some instance Binders are written in excess of 60 days AND in those instances the insurance company IS REQUIRED to send the insured a notice of the cancellation of the Binder.

Note: Binders of 60 days or less do not require formal notice of their cancellation/termination AND Binders 60 days or longer do require a formal notice of their cancellation/termination.

Risk

The term has also been used to mean the insured (”ABC Furniture is the risk we wrote the policy for”) or the exposure (“The policy covers the risk of fire”) among other definitions, but it is the chance of financial loss that we are concerned with in this course.

The courts typically favor which party in a lawsuit?

THE INSURED

Insurable Interest

The principle of indemnity is that one should not profit from the response provided by the policy. Without this principle, the fundamental purpose of insurance could be undermined by persons intentionally causing losses because it was to their economic advantage.

Although most property policies provide that loss payments will not exceed the “actual cash value” of the property, examples of apparent departure from strict adherence to the indemnity rule may be found: the policy may pay full replacement costs (meaning the insurer is “giving new for old”); the insurer may agree in advance that a specific amount is the agreed upon value and will be paid if the property is destroyed.

Notice we said “apparent” departure.

(1) If an insured is paid for a new roof when the old one blows off in a hurricane, it could be said the insured was “enriched”: But doesn’t the new roof, like the old one, simply keep out the elements? The safeguard employed by insurers is to require that actual replacement take place as a condition to paying for new when old is destroyed.

(2) When the insurer agrees in advance that it will pay a given amount for loss of a specific item, it is likely to require an appraisal that, in effect, establishes a fair value with no inducement for the insured to intentionally destroy the property.

(3) In the early history of liability insurance, the coverage indemnified (reimbursed) the insured for judgments. If the insured could not pay the judgment, there was nothing to indemnify. Modern liability policies recognize legal damages against the insured and pay directly to the claimant. This arrangement is considerably more acceptable to both the insured (who avoids bankruptcy) and the claimant (who has greater assurance of recovering full damages). Although some people have argued that this invites carelessness by the insured, it does not work against the principle underlying the rule of indemnity since the insured is protected from loss, not profiting from the policy response.

The Collector's Insurance

For her antique vase, valued at $50,000, Sarah opts for a valued policy. The insurer agrees that in the event of a covered loss, such as the vase being destroyed or stolen, they will pay a pre-agreed amount of $50,000. This policy is essential for Sarah as the vase’s market value might fluctuate, and finding a similar replacement could be impossible.

Sarah’s home insurance policy includes replacement cost coverage for personal property. When a fire damages her home, several pieces of her contemporary art are destroyed. The insurance company assesses that the cost to replace these art pieces is $100,000, which is higher than their depreciated actual cash value. Thanks to the replacement cost coverage, Sarah receives $100,000 from her insurer to replace the art pieces, rather than a lower amount that would have been based on their depreciated value.

For her vintage jewelry collection, valued at around $200,000, Sarah and her insurer agree on an “agreed value” coverage. This agreement states that in the event of loss or damage to the jewelry, the insurer will pay out $200,000, regardless of the fluctuating market value of the pieces at the time of the loss.

In each instance, these exceptions to the rule of indemnity ensure that Sarah is adequately compensated for the loss of items whose value might not be adequately reflected by their market price at the time of loss or by their original cost minus depreciation. These specialized insurance policies provide peace of mind and financial protection for her unique and valuable collection.

Which type of a hazard is ice on a sidewalk: physical, moral, or morale?

PHYSICAL HAZARD

Perils and Hazards

Hazards may be classified as physical, moral, or morale. A physical hazard is a condition stemming from the physical characteristics of an object that increases the probability and severity of loss from given perils. A moral hazard stems from the conscious mental attitude of the insured (e.g., intentional loss). A morale hazard stems from the unconscious mental attitude of the insured (e.g., accident proneness).

A good example to distinguish between a peril and a hazard in an insurance context could be a house fire. In this example, the peril is fire. A peril is a specific event or cause of loss covered by an insurance policy. In this case, it is the fire itself that damages or destroys the property.

A hazard, on the other hand, is a condition or situation that increases the likelihood or severity of the peril occurring. In the case of the house fire, a hazard might be faulty electrical wiring. While the wiring does not directly cause the loss, it increases the chances of a fire occurring.

This distinction is important in insurance because while insurance policies are designed to protect against perils (like fire, theft, flood), managing or mitigating hazards (like fixing faulty wiring, installing smoke detectors) is the responsibility of the policyholder to prevent losses from occurring in the first place.

The Case of the Slippery Banana Peel

In this sequence of events, Winston’s act of throwing the banana peel on the floor is the proximate cause of the subsequent mishaps, including Edgar’s fall and the spillage of the hot beverage on Pastor Jones and the others. It is considered the proximate cause because it was the initial action that led to all the subsequent events. Without Winston’s careless action, Edgar would not have slipped, and the spillage over Pastor Jones, Mrs. Jones, and the choir boys would not have occurred. Therefore, Winston’s action is seen as the root cause of the entire series of unfortunate events.

Direct and Indirect Loss Examples

| Event | Direct Loss | Indirect Loss |

| Fire Loss to Dwelling | Fire Loss to Dwelling | Two Week Hotel Rental |

| Automobile Collision | Collision Damage to Insured Vehicle | Loss of Use of the Car; Insured’s Three-Week Car Rental |

In the case of an Automobile Collision, the direct loss is the damage to the vehicle caused by the collision. The indirect loss includes the loss of use of the car and the expense of a rental vehicle for three weeks while the insured vehicle is being repaired.

Mortgage Clause Protections for Mortgagee

| Protection Aspect | Description |

| Loss Payments Distribution | Loss payments are payable to both the insured and the mortgagee up to the level of loss and in proportion to their level of economic interest in the property. |

| Right of Recovery | A mortgage company may have a right of recovery even if the insured has been denied. |

| Payment of Past Due Premiums | A mortgagee has the right to pay past due premiums to maintain the insurance coverage. |

| Notification of Policy Changes | The mortgagee is entitled to prompt notice of all policy non-renewals and cancellations. |

Mortgagee Clause

The second clause for mortgages highlights that in situations where the Insurer denies a claim that denial will not apply to a valid claim of the mortgagee, if the mortgagee:

- Notifies the Insurer of any change in ownership or substantial change in risk;

- Pays past due premiums; and

- Submit a signed sworn statement within 60 days of receiving notice of the Insured’s failure to do so.

The third clause for mortgages highlights that if the Insurer decides to cancel or not renew the policy, the mortgagee will be notified at least 10 days before the date of cancellation or nonrenewal is to take effect.

The fourth clause concerning mortgages states that if the Insurer pays the mortgagee for any loss and denies the Insured payment, the Insurer subrogates to all rights of the mortgagee granted under the mortgage on the property. According to Black’s Law Dictionary, “subrogation is the substitution for on party for another whose debt the party pays, entitling the paying party to rights, remedies or securities that would otherwise belong to the debtor” (Black’s Law Dictionary, 9th ed.). This allows for the Insurer to step in the shoes of mortgagee holding the same rights and remedies against the Insured that the initial mortgagee had. The second point states that at option of the Insurer, it may pay the mortgagee the whole principal on the mortgage plus accrued interest and in return receive a full assignment and transfer of the mortgage and all securities held as collateral to the mortgage debt.

In the second scenario, an Insurer will receive the complete assignment from the mortgagee, allowing for the transfer of all securities held as collateral to the mortgage debt.

Essentially in the first scenario, the Insurer steps into the shoes as the mortgagee and purchases the right to act as the new mortgagee and the second allows the rights in the mortgaged property to be assigned to the Insurer.

The fifth mortgage clause explains that just because an Insurer pays the mortgagee for any loss and subrogates, this will not impair any claim for recovery that the mortgagee was initially entitled to.

The Case of the Sleek Sedan

The aftermath of the collision was a disheartening sight. Ricky’s sedan, once a symbol of his hard work and pride, now lay crumpled and twisted beyond recognition. It was a bitter moment for Ricky, who had poured not just money, but also his heart into that car.

The insurance company declared the vehicle a total loss. The cost of repairing the car would far exceed its value, or it was simply beyond repair.

The insurance company evaluated the actual cash value (ACV) of Ricky’s sedan at $10,000. Ricky had always been diligent with his insurance and understood that his policy included a $500 comprehensive deductible. When he filed the claim for his totaled vehicle, the insurance company calculated his claim payment as $9,500 – the $10,000 value of the car less the $500 deductible.

Ricky had a deep attachment to his car and wanted to keep it despite its battered state. The insurance adjuster explained the concept of salvage value to Ricky. They assessed the salvage value of his damaged sedan at $800, representing the residual worth of the vehicle in its current state. If Ricky chose to keep the car, he would need to purchase it back from the insurance company for its salvage value.

Ricky pondered over his options. Eventually, his attachment to the car won over practicality. He decided to retain the vehicle and paid the insurance company $800 for its salvage. Thus, after the insurance payout and buying back the salvage, Ricky received a net amount of $8,700.

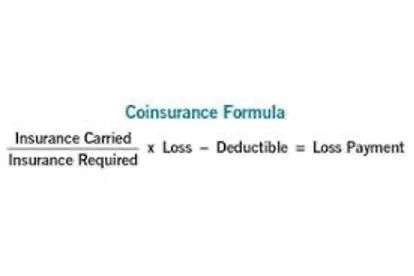

Coinsurance

Mr. Thompson’s homeowner’s policy included an 80% coinsurance clause. This clause meant that Mr. Thompson was required to maintain insurance coverage of at least 80% of the replacement cost of his home to avoid a penalty in the event of a claim. In Mr. Thompson’s case, this meant maintaining a minimum coverage of $800,000 ($1,000,000 x 80%).

Unfortunately, a fire caused significant damage to Mr. Thompson’s home, resulting in a loss of $300,000. Mr. Thompson, assured in the belief that his insurance would cover the damages, filed a claim with his insurance provider.

Where:

- Amount of Insurance Carried = $600,000

- Amount of Insurance Required = 80% of $1,000,000 (Home Value) = $800,000

- Loss Amount = $300,000

Despite suffering a loss of $300,000, due to the coinsurance clause and his decision to underinsure his home, Mr. Thompson received only $225,000 from his insurance provider. This outcome left him with a substantial out-of-pocket expense of $75,000 to cover the rest of the loss.

Mr. Thompson’s case is a cautionary tale about the importance of understanding the terms of an insurance policy, especially the implications of a coinsurance clause. This case underscores the necessity for policyholders to adequately insure their property in line with the coinsurance requirements to avoid significant financial burden in the event of a loss.

Scenario: High-Value Art Collection

Specific limits allow Mr. Anderson to insure each painting for its appraised value, ensuring that the more valuable pieces have higher coverage limits. If a particularly valuable painting is damaged or stolen, Mr. Anderson can be assured of receiving a payout that matches its specific appraised value, rather than being constrained by a blanket limit that may not fully cover the loss. For items with significantly different values, specific limits prevent overpaying for insurance on less valuable items while underinsuring the more valuable ones.

In this scenario, specific coverage limits provide Mr. Anderson with the peace of mind that each valuable piece in his collection is adequately insured for its individual worth.

Scenario: Real Estate Developer with Multiple Properties

In the event of a significant loss at one location, Ms. Garcia can utilize the aggregate coverage limit to fully address that loss, without being constrained by individual limits per building. Managing one aggregate coverage limit for all her properties simplifies Ms. Garcia’s insurance portfolio, making it easier to administer and track. Blanket coverage might offer a more cost-effective solution for insuring multiple properties, as it eliminates the need for detailed individual assessments and policies for each property.

For Ms. Garcia, a blanket coverage limit offers a more flexible and streamlined approach to insuring her diverse property portfolio, providing a safety net that can adapt to where the need is greatest.

The choice between specific and blanket coverage limits depends heavily on the nature of the assets being insured and the individual needs of the policyholder. High-value, distinct items may benefit more from specific limits due to their unique values, whereas a collection of assets with varying values and risks might be better served under a blanket coverage limit for its flexibility and efficiency.

Deductible Types

Sarah has an auto insurance policy with a straight deductible of $500. One day, she gets into a minor accident, and the total cost to repair her car is estimated at $2,000. Under her policy, Sarah is responsible for the first $500 of the repair costs (the deductible), and her insurance company will cover the remaining $1,500. If the repair cost had been $500 or less, Sarah would have had to pay the entire amount herself.

Percentage Deductibles Example: Homeowners Insurance in a Coastal AreaMark lives in a coastal area prone to hurricanes and has homeowners insurance with a 5% windstorm deductible. His home is insured for $300,000. When a hurricane damages his roof, causing $10,000 worth of damage, Mark’s deductible is calculated as 5% of his home’s insured value, which amounts to $15,000 (5% of $300,000). Since his deductible is higher than the damage cost, Mark would have to cover all the repair costs out of pocket.

Franchise Deductibles Example: Business Property InsuranceLinda owns a small bakery with a franchise deductible of $10,000 on her business property insurance. One night, a small fire caused damage to her bakery. The cost to repair the damages is estimated at $12,000. Since the damage exceeds her franchise deductible amount, the insurance company pays the entire $12,000. However, if the damage had been $9,500, below the franchise deductible threshold, Linda would have had to cover the entire cost herself, receiving no payout from her insurance.

- Straight Deductibles: These involve a fixed amount that the policyholder must pay per claim, like the $500 in Sarah’s auto insurance case.

- Percentage Deductibles: These are based on a percentage of the insured value, typically used in property policies covering hurricanes, as seen in Mark’s homeowners insurance.

- Franchise Deductibles: These come into play only when a loss exceeds a certain amount, and if it does, the insurer pays the full loss, as illustrated by Linda’s business insurance scenario.

Understanding these types of deductibles helps policyholders make informed decisions about their insurance coverage and assess their willingness to share the risk with their insurance company.

In a liability insuring agreement, what kind of obligation must the insured have before the insurer is required to pay on behalf of the insured?

LEGAL OBLIGATION TO A THIRD PARTY

[Date]

[Insured’s Name][Insured’s Address][City, State, ZIP Code]

Re: Excess Ad Damnum Notification

Policy Number: [Policy Number]Claim Number: [Claim Number]Claimant: [Claimant’s Name]

Dear [Insured’s Name],

I am writing to you in regard to the recent claim filed by [Claimant’s Name] concerning the incident that occurred on [Date of Incident], involving [brief description of the incident].

As per our review and the subsequent legal proceedings, the claim amount sought by [Claimant’s Name] has exceeded the liability limits of your insurance policy under [Insurance Company]. Your current policy, [Policy Name/Number], provides coverage up to [Policy Limit Amount], which is the maximum amount we can allocate towards this claim.

It is important to note that the claimant’s demand currently stands at [Claim Amount], which surpasses your policy’s coverage limit by [Excess Amount]. This excess amount is beyond the scope of your insurance policy’s coverage and may become your personal financial responsibility.

We understand that this information may be of concern to you. We want to assure you that our legal team is diligently working on your behalf in this matter and is committed to representing your interests up to the limits of your policy. However, considering the potential financial implications, we strongly recommend that you seek independent legal counsel to advise you on how to proceed with the portion of the claim that exceeds your policy limits.

Please understand that this notification is a standard procedure and is intended to keep you fully informed of the developments in your case. It is also to ensure that you are aware of your potential financial responsibilities in this matter.

If you have any questions or require additional information, please do not hesitate to contact us at (555) 555-5555.

Sincerely,

[Claims Adjuster]

[Adjuster Title]

[Insurance Company]

[Contact Information]

There are three main duties the insured must fulfill when filing an insurance claim; can you name them?

PROMPT NOTICE OF LOSS - COOPERATE WITH INSURER - PRESERVE THE INSURER'S RIGHTS

The Smith Family’s Loss

The Smiths filed a claim with their homeowners insurance company, HomeGuard Insurance. After assessing the damage, HomeGuard Insurance determined that the claim was valid and covered under the Smiths’ policy. They compensated the Smiths for the damage to their home and personal property, which amounted to $150,000. This payment helped the Smiths to start rebuilding their home and replace their lost belongings.

HomeGuard Insurance’s investigation revealed that the cause of the fire was a manufacturing defect in the clothes dryer. With this information, HomeGuard decided to pursue subrogation against SuperDry, the manufacturer of the dryer.

By paying the Smiths’ claim, HomeGuard Insurance acquired the legal rights to seek recovery from SuperDry for the faulty appliance that caused the fire. HomeGuard Insurance initiated legal action against SuperDry, seeking reimbursement for the claim amount they paid to the Smiths. After negotiations, SuperDry agreed to a settlement, acknowledging the manufacturing defect in the dryer. They compensated HomeGuard Insurance for the full amount of the claim paid to the Smiths.

With the successful recovery of funds from SuperDry, HomeGuard Insurance was able to recoup the costs of the claim. Additionally, they reimbursed the Smiths for their deductible and any other out-of-pocket expenses incurred due to the loss.

In this scenario, the subrogation clause in the Smiths’ homeowners insurance policy allowed HomeGuard Insurance to “step into their shoes” and seek recovery from SuperDry, the party responsible for the loss. This process not only helped the Smiths by compensating them for their loss but also allowed HomeGuard Insurance to hold the responsible party accountable. Subrogation, in this case, prevented double recovery and contributed to the overall effectiveness of the insurance system by ensuring that costs are borne by those responsible for the loss.

How will the policies respond to the $100,000 claim if the "Other Insurance" clause in each policy states Pro-Rata Shares?

$33,333 of the loss ($500,000/$1,500,000 X $100,000 loss)

$66,667 of the loss ($1,000,000/$1,500,000 X $100,000 damages)

No, the claimant's recovery will be relegated to their total damages of $100,000.

Other Insurance Provision

Their second policy, with Alpha-Omega Insurance, has higher limits of $25,000 per person and $50,000 per accident. Both policies contain an “Other Insurance” clause and specify coverage on an “equal shares” basis.

While driving, Tom is involved in an accident where the other driver is injured. The injury claim from the other driver amounts to $30,000. Both Ajax and Alpha-Omega are notified of the claim. Given the “equal shares” basis stipulated in their “Other Insurance” clauses, the insurers must coordinate to cover the claim.

The total coverage from both policies combined is $35,000 per person ($10,000 from Policy A + $25,000 from Policy B).

Since the policies state that they cover on an “equal shares” basis, each insurer contributes equally to the claim, up to their respective policy limits.

The total claim is $30,000. Both insurers split this amount equally, with each paying $15,000.

However, Insurer A’s policy limit per person is $10,000. Therefore, Insurer A pays $10,000, and Insurer B pays the remaining $20,000 to fully cover the $30,000 claim.

In this example, the “Other Insurance” clause, along with the specific provision for “equal shares” coverage, guided the resolution of the claim. In this example it was a good thing that Tom and Linda had two policies as the damages exceeded the limits of either policy. The claim was split between the two insurers, but within the limits of their respective policy coverages. This scenario demonstrates the importance of understanding the intricacies of insurance policy clauses, especially when multiple policies are involved. It ensures that the insured is adequately covered without overstepping the bounds of either policy.

Liberalization Clause

The initial policy had a specific provision for living expenses coverage, which reimbursed the couple for additional living costs if their home became uninhabitable due to a covered peril. The coverage limit for these additional living expenses was set at $5,000.

In March 2024, Homestead Insurance adopted a new policy revision, which broadened the living expenses coverage. The new revision increased the coverage limit for additional living expenses from $5,000 to $10,000, without any additional premium. This change was part of an effort by Homestead Insurance to offer more competitive and comprehensive coverage to their clients.

In April 2021, a severe storm hit Tom and Linda’s neighborhood, causing significant damage to their home and making it temporarily uninhabitable. The couple was forced to stay in a rental property while repairs were made to their home.

When Tom and Linda filed a claim for their additional living expenses, they were initially concerned about exceeding the original $5,000 coverage limit. However, due to the liberalization clause in their policy, they benefited from the recent policy revision by Homestead Insurance. Tom and Linda submitted their claim, which totaled $6,500 in additional living expenses.

Despite their policy initially having a $5,000 limit, the liberalization clause allowed them to benefit from the enhanced coverage limit of $10,000. Therefore, their claim of $6,500 was fully covered without any additional premium.

In this scenario, the liberalization clause in Tom and Linda’s homeowners policy allowed them to benefit from improved coverage terms that Homestead Insurance introduced after the start of their policy period. As a result, their claim for additional living expenses due to the storm damage was fully covered under the enhanced limit, even though this broader coverage was not part of their original policy terms when they renewed it.

This example illustrates how the liberalization clause can provide policyholders with additional benefits at no extra cost, reflecting the insurer’s commitment to offer the best possible coverage terms to their clients.

Florida Non-Renewal Requirements

| Scenario | Notice Period Required | Additional Requirements |

| General Policy Non-Renewal (Standard Scenario) | 45 days | Reason for non-renewal must be stated on the notice. |

| Failure to Provide Timely Notice | Until 45 days after notice is given | Coverage remains in effect until 45 days after the notice is eventually given. |

| Non-Renewal of Personal Lines or Commercial Residential Property Insurance | 120 days | Reason for non-renewal must be included. |

| Non-Renewal Following Emergency Damage | 90 days after repairs are completed | Applicable for properties damaged by a loss classified as an “emergency” by the Commissioner of Insurance Regulation. |

Types of Reinsurance

Non-proportional Reinsurance: the insurer and reinsurer establish a price for the reinsurance contract and the exposure to loss is based upon a threshold to loss incurred by the insurer; the reinsurer pays all loss amounts after the threshold has been pierced.

One additional type of reinsurance, Facultative Reinsurance, is also used but is much more limited in scope. With facultative reinsurance, the insurer negotiates on a risk-by-risk basis for each exposure and the reinsurer is not obligated to accept any/all of the offered risk.

The Case of “Where Are You When I Need You?”

Robert must file his hurricane damage claim with FIGA, following the same process as he would with his original insurer. The Florida Insurance Guarantee Association (FIGA) steps in to handle claims from insolvent insurance companies. FIGA’s role is to provide a safety net for policyholders in such situations.

FIGA assesses the claim to ensure its validity. This involves verifying the damage, the policy coverage, and the terms of the policy under which Robert was insured. Although Robert’s home is insured for $750,000, FIGA has statutory coverage limits. For homeowner’s policies, FIGA covers up to $300,000 for property damage. The damage to Robert’s home is assessed at $500,000. After assessing the damage and deductibles, FIGA calculates the claim payment within the statutory limits. Unfortunately, Robert does not receive full reimbursement for his entire loss.

Robert’s damages significantly exceed FIGA’s statutory limits; his only recourse is to seek compensation through the liquidation proceedings of his insolvent insurer (a lengthy and uncertain process).

Post-claim, Robert needs to find a new insurance provider for future coverage, as FIGA’s role is only to handle claims and not to provide ongoing insurance coverage.

In summary, FIGA serves as a crucial protection mechanism for policyholders like Robert Boneski when their insurer becomes insolvent. However, it’s important to note that FIGA’s coverage is subject to statutory limits, which might not fully cover all losses, especially in high-value claims.

What must a misrepresenation or concealment "be" to lead to a claim denial?

FRAUDULENT OR MATERIAL TO THE RISK

The Case of “To Tell the Truth”

In the same application, John states that his house is a masonry home. However, in reality, his house is 100% frame, which he chose not to disclose to earn a lower premium. This false statement is a misrepresentation. Under Florida law, this misrepresentation would not necessarily lead to a claim denial unless it’s proven fraudulent or materially affects the risk assumed by the insurer.

Additionally, John knows that there’s an ongoing issue with his home’s electrical wiring that poses a significant fire hazard. However, he fails to disclose this when applying for insurance. This omission is an example of concealment. Similar to misrepresentation, under Florida law, concealment will not automatically result in a claim denial unless it meets certain criteria like being fraudulent or materially affecting the risk.

In summary, while a warranty is a condition of the policy itself and its breach can lead to claim denial, misrepresentation, and concealment, per Florida statutes, would only lead to claim denial if they: (1) are fraudulent; (2) materially affect the risk; or (3) had they been known, would have led the insurer to either not issue the policy or issue it under different terms.

Key Differences: Catastrophic Ground Collapse vs. Sinkhole

Coverage: Catastrophic ground collapse is statutorily required under standard policies, whereas sinkhole coverage is optional and requires a separate purchase or endorsement.

Damage Verification: Catastrophic ground collapse is visually apparent and involves immediate and severe damage, whereas sinkhole damage might require professional geological assessment to verify.

What are the Fungi limits in a typical Florida policy?

$10,000 PER LOSS/$20,000 PER POLICY PERIOD

When can Hurricane Deductibles be changed in an insurance policy?

ONLY AT A POLICY'S RENEWAL

HOMEOWNER CLAIMS BILL OF RIGHTS

YOU HAVE THE RIGHT TO:

- Receive from your insurance company an acknowledgment of your reported claim within 7 days after the time you communicated the claim.

- Upon written request, receive from your insurance company within 30 days after you have submitted a complete proof-of-loss statement to your insurance company, confirmation that your claim is covered in full, partially covered, or denied, or receive a written statement that your claim is being investigated.

- Your insurance company shall provide you with a copy of any detailed estimate of the amount of the damage within 7 days after the estimate is generated by the insurance company’s adjuster.

- Within 60 days, subject to any dual interest noted in the policy, receive full settlement payment for your claim or payment of the undisputed portion of your claim, or your insurance company’s denial of your claim.

- Free mediation of your disputed claim by the Florida Department of Financial Services, Division of Consumer Services, under most circumstances and subject to certain restrictions.

- Neutral evaluation of your disputed claim, if your claim is for damage caused by a sinkhole and is covered by your policy.

- Contact the Florida Department of Financial Services, Division of Consumer Services’ toll-free helpline for assistance with any insurance claim or questions pertaining to the handling of your claim. You can reach the Helpline by phone at (toll-free phone number), or you can seek assistance online at the Florida Department of Financial Services, Division of Consumer Services’ website at (website address).

YOU (Policyholders) ARE ADVISED TO:

- Contact your insurance company before entering into any contract for repairs to confirm any managed repair policy provisions or optional preferred vendors.

- Make and document emergency repairs that are necessary to prevent further damage. Keep the damaged property, if feasible, keep all receipts, and take photographs of damage before and after any repairs.

- Carefully read any contract that requires you to pay out-of-pocket expenses or a fee that is based on a percentage of the insurance proceeds that you will receive for repairing or replacing your property.

- Confirm that the contractor you choose is licensed to do business in Florida. You can verify a contractor’s license and check to see if there are any complaints against him or her by calling the Florida Department of Business and Professional Regulation. You should also ask the contractor for references from previous work.

- Require all contractors to provide proof of insurance before beginning repairs.

- Take precautions if the damage requires you to leave your home, including securing your property and turning off your gas, water, and electricity, and contacting your insurance company and provide a phone number where you can be reached.

What is the over-arching importance of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act?

GLBA REQUIRES INSURANCE COMPANIES TO SAFEGUARD THEIR CUSTOMER'S SENSITIVE DATE

Personal Injury Protection

Since both Alice and Bob are insured individuals covered by PIP through their respective auto insurance policies, they can each access PIP benefits to cover their medical expenses and lost wages resulting from the accident. Alice will file a PIP claim with her insurance company and Bob will file a claim with his parents insurance company. The driver of the other vehicle will also file a PIP claim with their insurance company. It doesn’t matter who was driving or which vehicle they were in at the time of the accident; PIP benefits follow the insured individual.

Alice and Bob have immunity for the other driver’s injuries up to $10,000. Because Alice’s vehicle is insured; both Alice, the owner, and Bob, the driver, have immunity for up to $10,000 of the other driver’s injuries.

So, while both Alice and Bob can access PIP benefits regardless of the vehicle they were in, tort immunity protections primarily apply to the vehicles and their associated individuals involved in the accident.

No PIP/No Immunity

Because Alice did not carry PIP coverage on her vehicle: she, as the owner; and Bob, as the driver; are both responsible for the other driver’s injuries including any pain and suffering, lost wages, and other injury related claims he can file. Both Alice and Bob are subject to loss of their driver license, and for Alice her car’s registration.

PIP Claim Calculation

Alice’s injuries total $8,000; and she will be paid $6,400 by her insurance company. Calculated as:

[$8,000 – $0] X 80% = $6,400

If, Alice had a $500 PIP deductible her claims payment would be $6,000.

[$8,000 – $1,000] X 80% = $6,000

And if she had a $1,000 PIP deductible her claims payment would be $5,600.

[$8,000 – $1,000] X 80% = $5,600

PIP Coverage for the Named Insured – In and Out of Florida. Does it matter?

Now image that Alice Shirley, a Florida resident, is visiting her friend in Georgia. While riding in her friend’s car, they are involved in an accident that causes Alice to suffer $8,000 in injuries. Unfortunately, Alice’s injuries are not covered by her PIP coverage. Florida PIP coverage extends to the insured when they are outside of the state of Florida only when the insured is in their own vehicle or in a vehicle owned by a resident relative.

PIP Coverage for Residing Relatives – In and Out of Florida. Does it matter?

Alice’s injuries total $8,000; and she will be paid $6,400 by her insurance company. Calculated as:

[$8,000 – $0] X 80% = $6,400

Betty’s injuries total $5,000; and she will be paid $4,000 by her insurance company. Calculated as:

[$5,000 – $0] X 80% = $4,000

Now image that Betty was visiting a friend in Georgia. While riding in the friends car, Betty and her friend are involved in an accident that causes Betty to suffer $5,000 in injuries. Betty’s injuries would not be covered under her daughter’s PIP coverage; she is a residing relative to be sure, but the accident occurred outside of the state of Florida and Betty was not injured while occupying the named insured’s vehicle.

If that same accident had occurred in Georgia and Betty was in Alice’s car then her medical expenses would have been covered by Alice’s PIP coverage.

Tort Exempt?

Under Florida’s No-Fault law, John’s Personal Injury Protection (PIP) coverage will initially cover his medical expenses and lost wages (limits apply), regardless of who was at fault in the accident. Therefore, John’s PIP coverage will pay for his medical bills and any lost income while he recovers from his injuries.

However, Sarah, the other driver, suffers from severe whiplash and experiences significant pain and suffering due to the accident. Sarah’s injuries meet one of the PIP exceptions, specifically the “significant and permanent loss of a bodily function.” As a result, Sarah can pursue legal action against John beyond her own PIP coverage limits to seek compensation for her pain, suffering, and other non-economic losses.

In this scenario, although John is initially protected by PIP coverage, Sarah’s injuries meet the threshold for exceptions outlined in Florida’s No-Fault law, allowing her to file a legal claim against John for additional damages beyond what PIP covers.

PAP Eligible Insureds and Vehicles

| Insureds | Eligible |

| Individuals | Yes |

| Related persons | Yes |

| Unrelated persons who reside together | Yes |

| Vehicles | Eligible |

| Private passenger autos | Yes |

| Pickups & Vans with gross vehicle weight under 10,000 pounds | Yes (not used for goods/materials) |

PAP – “Your Covered Auto”

| Category | Coverage |

| Vehicle listed in the policy’s Declarations | Yes |

| Newly acquired autos | Yes |

| Owned trailers | Yes |

| Non-owned auto or non-owned trailers used as temporary replacement | Yes |

- Breakdown

- Repair

- Servicing

- Loss

- Destruction

Keep in mind that a “your covered auto” does not have coverage for physical damage to these vehicles.

- We will pay damages for “bodily injury” or “property damage” for which any “insured” becomes legally responsible because of an auto accident. Damages include prejudgment interest awarded against the “insured”. We will settle or defend, as we consider appropriate, any claim or suit asking for these damages. In addition to our limit of liability, we will pay all defense costs we incur. Our duty to settle or defend ends when our limit of liability for this coverage has been exhausted by payment of judgments or settlements. We have no duty to defend any suit or settle any claim for “bodily injury” or “property damage” not covered under this policy.

Reclamación de conductores sin seguro

La recuperación de UM de Bert se calcula de la siguiente manera:

Daños totales: $50,000

Menos recuperación de PIP: $10,000

Menos la recuperación de la cobertura del seguro de responsabilidad civil: $10,000

Bert puede cobrar los $30,000 restantes en daños bajo su cobertura para conductores sin seguro.

Stacked Uninsured Motorists Claim

Bert’s UM recovery is calculated as follows:

Total damages: $250,000

Minus PIP recovery: $10,000

Minus liability insurance coverage recovery: $10,000

Bert can collect $100,000 in damages under his Uninsured Motorists coverage. Bert’s UM coverage is $50,000 per person and it is stacked; basically, he has $50,000 per person + $50,000 per person for a total of $100,000 of Uninsured Motorist coverage. Unfortunately for Bert he only carried $50,000 per person of UM coverage; and thankfully he did his UM coverage stacked so he was able to collect an extra $50,000 of UM coverage.

What if the coverage was different? If Bert Scott sustains permanent injuries due to an accident caused by Earnie. Bert’s total damages (economic and non-economic) amount to $250,000. Bert is covered by Personal Injury Protection (PIP) insurance, from which he has already received the full $10,000 limit. But in this scenario Bert has stacked Uninsured Motorist (UM) coverage with a limit of $100,000/$300,000, and Bert has two vehicles on his policy. Earnie, the at-fault driver, has liability insurance with limits of 10/20/10.

Bert’s UM recovery is calculated as follows:

Total damages: $250,000

Minus PIP recovery: $10,000

Minus liability insurance coverage recovery: $10,000

Bert can collect $200,000 in damages under his Uninsured Motorists coverage. Bert’s UM coverage is $100,000 per person and it is stacked; basically, he has $100,000 per person + $100,000 per person for a total of $100,000 of Uninsured Motorist coverage. Unfortunately for Bert he only carried $100,000 per person of UM coverage; but thankfully he did his UM coverage stacked so he was able to collect an extra $100,000 of UM coverage.

Non-Stacked Uninsured Motorists Claim

Bert’s UM recovery is calculated as follows:

Total damages: $250,000

Minus PIP recovery: $10,000

Minus liability insurance coverage recovery: $10,000

Bert can collect $50,000 in damages under his Uninsured Motorists coverage. Bert’s UM coverage is $50,000 per person and it is non-stacked; basically, he has $50,000 per person for a total of $50,000 of Uninsured Motorist coverage.

What if the coverage was different? If Bert Scott sustains permanent injuries due to an accident caused by Earnie. Bert’s total damages (economic and non-economic) amount to $250,000. Bert is covered by Personal Injury Protection (PIP) insurance, from which he has already received the full $10,000 limit. But in this scenario Bert has non-stacked Uninsured Motorist (UM) coverage with a limit of $100,000/$300,000, and Bert has two vehicles on his policy. Earnie, the at-fault driver, has liability insurance with limits of 10/20/10.

Bert’s UM recovery is calculated as follows

Total damages: $250,000

Minus PIP recovery: $10,000

Minus liability insurance coverage recovery: $10,000

Bert can collect $100,000 in damages under his Uninsured Motorists coverage. Bert’s UM coverage is $100,000 per person and it is non-stacked; he has $100,000 per person of Uninsured Motorist coverage.

The Case of the Non-Owned Auto

The pickup truck lent to John by his friend Tom would be considered a “non-owned auto” under John’s PAP. This is because the pickup truck is not owned by John or furnished for his regular use but is temporarily being used by him.

If instead of borrowing the pickup truck from his friend, John decided to rent a pickup truck from a car rental agency for the same purpose, that rented pickup truck would be considered a “hired auto” under John’s PAP. This is because the pickup truck is not owned by John or furnished for his regular use but is specifically hired by him for a temporary period with a formal rental agreement.

In summary, while both terms refer to vehicles not owned by the insured, “hired autos” are intentionally rented or borrowed for a specific purpose with formal agreements like rentals or leases. “Non-owned autos” are used more incidentally and are not typically vehicles that the insured would use regularly or have formal rental agreements for.

Homeowners Perils Insured Against

| Policy | Perils Insured Against |

| HO-2 | named perils for all Section I Coverages |

| HO-3 | "all-risk" coverage for Coverages A&B and named perils of HO-2 for Coverage C |

| HO-4 | named perils for all Section I Coverages |

| HO-5 | "open" perils coverage for Coverages A, B, & C (broadest form available) - keep in mind that "open perils" and "all risk perils" are the same. |

| HO-6 | named perils coverage |

| HO-8 | first (10) HO-2 named perils + volcanic eruption and catastrophic ground collapse; residence premises theft limited to $10,000 and building glass breakage limited to $100 |

The Nassar Hurricane Claim

Their insurer valued the damage to their dwelling at $20,090.61 and the damage to their other structures at $70,449.02 but paid up to the policy limits for Coverage B, which in this case was $24,720.

The Nassars, however, believed that their fencing should be considered as part of the dwelling because it was attached to it. The policy does not define “structure,” and their fencing, they pointed out, was attached to their house at four separate points. The insurer, on the other hand, objected that “simply connecting 4,000 feet of fencing to the dwelling by four bolts does not attach the fencing to the dwelling.” Since the policy states that a fence cannot connect the dwelling to other structures, the fence itself must be an “other structure.”

The trial court found in favor of the insurance company. When the Nassars appealed, the court of appeals agreed with the trial court, but with a dissent that argued that the policy was ambiguous and that a decision should therefore have been made in favor of the Nassars. The Supreme Court then heard the case.

Based on dictionary definitions, it concluded that the fence was a structure, “composed of parts purposefully joined together,” and that it was attached, since it was “fastened to the dwelling either by being cemented to the brick and slab of the house (as the Nassars contend) or by ‘four bolts’ (as the insurance company contends). “Putting everything together and giving words their ordinary meaning in light of their common usage, the Nassars’ fencing is composed of parts purposefully joined together and fastened to the dwelling by bolts or cement…. We conclude that the Nassars’ policy interpretation is reasonable, and the applicable policy language is unambiguous.”

The court went on to note that the fencing did not fall under “other structures,” because the policy says that “other structures” are “set apart from the dwelling by clear space” and the fencing was not.

But, said the insurance company, if a fence attached to the dwelling is considered part of the dwelling and the fence is also attached at the other end to a barn, then the barn would also be attached to the dwelling—and that is exactly what the policy explicitly denies when it defines “other structures” as including “structures connected to the dwelling by only a fence.” Therefore, the fence cannot be included in the dwelling and must be seen as an “other structure” itself.

The court rejected this line of argument. It is true that the barn is not part of the dwelling since it is connected to the dwelling by only a fence. But that does not mean that the fence is not part of the dwelling. The Nassars’ fencing, “a structure clearly attached to their dwelling” so that it should be covered with the dwelling, is not required “to morph into an ‘other structure’ … simply because that same fencing cannot operate to connect other structures to the dwelling.”

But are all 4000 feet of fencing part of the dwelling? That said, the court, stated it was a matter for the trial court to resolve. “A fact finder may determine that only the fencing of the type originally bolted to the dwelling is covered” with the dwelling, whereas the pens and garden fencing and so on are “other structures.” Or perhaps, just as a barn connected to the dwelling by only a fence is an “other structure,” so a section of fence connected to the dwelling by only a section of fence should be considered an “other structure.” “Courts may have to treat fencing as both part of the ‘dwelling’ and ‘other structures’ depending on the circumstances. That is what the policy’s plain language requires.”

The court concluded that the Nassars’ interpretation of the policy was reasonable, and the insurance company’s was not, that there was no ambiguity, and that the trial court and court of appeals had both erred. It reversed the court of appeals’ judgment and remanded the case to the trial court for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.

The Case of the Knight Storm

As a result of the covered peril (windstorm damage), Mary and John’s residence is deemed unfit for occupancy by local authorities and their insurance company. Fortunately, their ISO Homeowners Insurance policy includes Coverage D – Loss of Use.

Mary and John are forced to temporarily relocate to a nearby hotel while their home is being repaired. The insurance company covers the additional living expenses incurred by Mary and John during this period, such as hotel bills, restaurant meals, and laundry expenses, allowing them to maintain their normal standard of living despite the displacement.

Mary and John also rent out a portion of their home to tenants. Since the rented portion is now uninhabitable due to the storm damage, the insurance company reimburses them for the fair rental value of that space, less any expenses that do not continue while it remains unfit for occupancy. This ensures that Mary and John do not suffer financial loss due to the inability to collect rental income.

If local authorities prohibit Mary and John from accessing their home due to safety concerns stemming from the neighboring damage caused by the windstorm, Coverage D would also apply. The insurance company would cover the additional living expenses and fair rental value for up to two weeks while the civil authority prohibits access to the property.

In this example, Coverage D – Loss of Use provides Mary and John Knight with financial assistance to cover the temporary increase in living expenses and rental income loss incurred as a result of their home being rendered uninhabitable by a covered peril.

What is the minimum Loss Assessment coverage requirement for an HO-6 Condo Policy?

$2,000

The Case of Pfenning v. Lineman

After several such trips around the course, Pfenning was suddenly struck in the mouth by a golf ball. Joseph Lineman, about eighty yards away, had hit the ball. The low drive was straight for the first sixty or seventy yards and then hooked to the left toward the cart. Lineman shouted “fore,” but Pfenning did not hear it. The golfer heard a “yelp” and ran after the ball and found that it had struck Pfenning, who suffered injuries to her mouth, jaw, and teeth.

Pfenning filed a damage action against Lineman among others. The trial court granted summary judgment in favor of all of the defendants, and Pfenning appealed. The court of appeals affirmed the trial court’s judgment. The case came to the Supreme Court, where Pfenning argued again that summary judgment was inappropriate because there were genuine disagreements about the facts.

The golfer, Joseph Lineman, argued that “he could not be held liable under a negligence theory because [Pfenning] was a co-participant in the sporting event, and her injuries resulted from an inherent risk of the sport.” The court recognized that to establish a claim of negligence, a plaintiff must establish that there was (1) a duty owed to the plaintiff by the defendant, (2) a breach of the duty, and (3) an injury proximately caused by the breach of duty.” The court also affirmed that public policy encourages participation in athletic activities and therefore discourages “excessive litigation of claims by persons who suffer injuries from participants’ conduct.”

The court concluded that, “in negligence claims against a participant in a sports activity, if the conduct of such participant is within the range of ordinary behavior of participants in the sport, the conduct is reasonable as a matter of law and does not constitute a breach of duty.” The court recognized, though, that “a participant’s particular conduct may exceed the ambit of such reasonableness as a matter of law if the ‘participant either intentionally caused injury or engaged in [reckless] conduct.’”

In this case, Lineman’s “hitting an errant drive which resulted in [Pfennig’s] injury … is clearly within the range of ordinary behavior of golfers and thus is reasonable as a matter of law and does not establish the element of breach required for a negligence action.” Pfenning argued that golf etiquette required shouting “fore” and that, while Lineman said he said and some others testified that they heard him, Pfenning herself did not hear him. The court recognized that a number of factors could have prevented her hearing Lineman, that yelling “fore” or not doing are both within ordinary golfing behavior, and therefore that “neither the omission nor manner of yelling ‘fore’ can be a proper basis for a claim of negligence in golf ball injury cases.”

The court therefore affirmed the previous courts’ decisions that Lineman was not negligent and therefore was not liable for Pfenning’s injuries.

The Case of Sierfeld v. Sierfeld

The insurance policy specifically excluded coverage for damages for an insured, defined to include a resident relative, and for medical expenses for “bodily injury to any insured person or regular resident of the insured premises.” The policy did not define “resident.”

The insurer denied coverage and sought summary judgment from the court on the basis of these exclusions. Jamie argued in response that the policy exclusions were ambiguous because they did not define “resident,” and therefore they must be read in such a way as to provide coverage for her. Alternatively, she said, she should not be considered a resident of her parents’ home because neither she nor her parents intended her to live there long-term. She had, in fact, moved into their house temporarily after losing her job, had planned to start her own business, and had intended to stay only six months—though she ended up staying longer after her injuries.

The trial judge mistakenly thought that the Sierfelds had given up their argument based on ambiguity, and so he focused only on whether Jamie was a resident of her parents’ home. He noted that both Jamie and her parents intended her stay to be temporary but also that “the arrangement was informal, flexible and without any specific duration … no different from any child living as a family member of a parents’ home.” She paid no rent or utility costs. She had meals occasionally with her family, though she purchased her own food because she, unlike her parents, was a vegetarian. He concluded that she “had sufficient connection to the insured premises to be considered a resident member of that household.”

When Jamie appealed, she raised the issue of ambiguity again and argued that her and her parents’ intention that her stay be temporary should have led the court to conclude that she was not a resident of her parents’ household. The Superior Court did not accept that the term “resident” in the policy was ambiguous. Whether someone is a resident of a household, they said, citing previous cases, was not simply a matter of whether he or she lived under the same roof but rather whether there was a “substantially integrated family relationship” between the insured and the party seeking coverage—in this case, between the Sierfelds and Jamie herself.

The court concluded that there was. “Among other things, [Jamie] enjoyed a relationship with the Sierfelds as a family member; she had no rental agreement and did not pay rent or utilities or contribute to household expenses; she had no set plan to move at the time of the dog bite and could have stayed with her parents beyond the six-month period; she had common use of the bathroom, kitchen and laundry room; and her driver’s license contained her parents’ address, her car was insured and registered there and she received her personal mail there. [Her] use of a bedroom other than her childhood bedroom, and her lack of socializing or sharing meals with her parents or rarely watching television with them does not compel a contrary conclusion.”

The court therefore affirmed the trial court’s decision that she was indeed a resident of her parents’ household.

Exceptions to the Motorized Land Conveyances Exclusion

| Exception | Coverage |

| Vehicles in Dead Storage and those used to service the residence | COVERED |

| Golf Carts at the Insured Location and Golf Course | COVERED |

| Owned Off-road Recreational Vehicles (RV) at residence premises | COVERED |

| Non-owned RVs Worldwide | COVERED |

| Vehicles to Assist the Handicapped | COVERED |

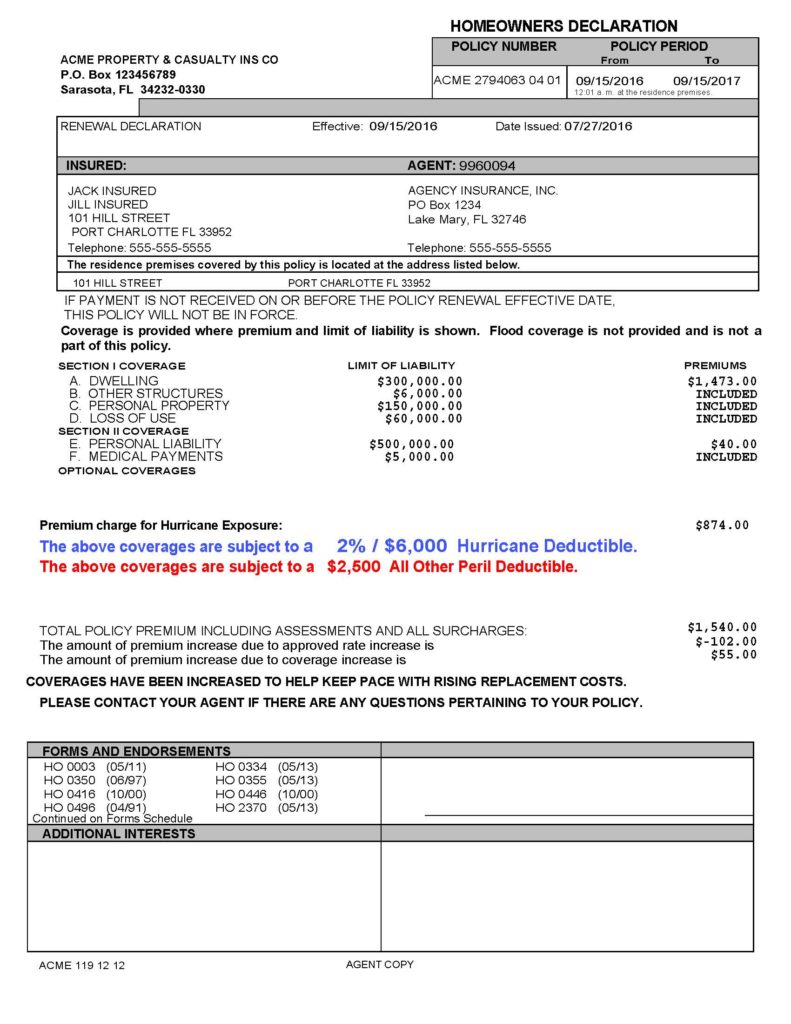

Declarations Page Example

What is the purpose of Wind Mitigation?

TO HELP A STRUCTURE WITHSTAND OR INCREASE RESISTANCE TO HIGH WINDS CAUSED BY MAJOR STORMS OR HURRICANES.